Plato and Moral Psychology

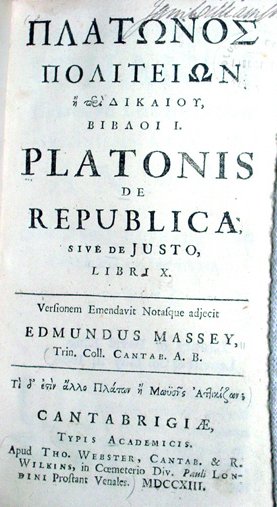

Plato (427-334 BC) recorded perhaps the oldest surviving model of moral psychology in the western tradition. His ideas appear in his Dialogues, and we will concentrate mostly on The Republic.

While his ideas on man’s moral motivations have been surpassed by more recent philosophers and psychologists (and therefore seem almost quaint today), it’s interesting to see prescient echoes of his ideas in modern life.

The Tripartite Soul

Plato started his argument by assuming that humans contain an eternal soul responsible for our desires. He then argued that this soul has three parts.

The first is the logical part, which allows us to separate what is real from what merely seems real through reason. This part of the soul desires truth and loves goodness.

Next is the spirited part of the soul, which is competitive and seeks honor and victory.

Finally is the appetitive part of the soul, which gives us our more base desires. This appetitive part can be concerned with three kinds of appetites: those which are necessary (e.g. simple foods for nutrition), those which are superfluous but permissible (e.g. luxuries), and those which are lawless (e.g. theft).

As In the City, So In the Man

The Republic is ostensibly a search for the definition of “justice.” Plato, however, finds an interesting way of seeking this definition. He starts by assuming that there is a direct analogy between a just man and a just society, one simply being a macro view of the other. He then sketches a utopian society so that he can “more easily see” what is justice in this larger view. Finally, he extrapolates the definition of justice for an individual by its analogy to justice within larger society.

Plato links five regime archetypes to the concerns of the tripartite soul, and demonstrates a relationship between a state of a certain temperament and a man of that same temperament. For example, he argues there is a relationship between a tyrannical state and a man ruled by lawless appetites.

These are the five regimes:

- Aristocracy, which relates to the logical soul (rule by the best – philosopher kings)

- Timocrasy, which relates to the spirited soul (rule by the honored – great soldiers)

- Oligarchy, which relates to the necessary appetites (rule by the few – the wealthiest merchants)

- Democracy, which relates to the superfluous appetites (rule by the many)

- Tyranny, which relates to the unlawful appetites (rule by the tyrant)

It’s interesting to see democracy so far down on the list, considering how we worship it in modern times. Plato had a narrow conception of who was fit to rule. Able rulers belonged to a certain class of society by birth, temperament and education. Soldiers belonged to a separate, second class. Workers and common men belonged to inferior classes, and because of their fickle, uneducated nature, they could bring about ruin if they were allowed to rule. Socrates’s death, Plato would note, was put to a vote.

‘Cratic Degeneration

Plato next demonstrates how each level of regime, should it falter, could degenerate into the next:

- Aristocracy devolves into timocracy when the next generation of leaders comes from an inferior class, preferring spirited if simple-minded rule suited mostly for war.

- Timocracy devolves into oligarchy when Timocrat leaders begin to see accumulation of wealth as a virtue, thrilling themselves with hoarding and waste.

- Oligarchy devolves into democracy when the populace begins to worship individual freedoms, and become consumed with superfluous desires .

- Democracy devolves into tyranny when it becomes so individualist as to plunge into chaos, and from this chaos a charismatic man seduces the people with promises and then rules with complete caprice.

Within these descriptions, we can already see chilling parallels to contemporary cultures.

A just man, Plato concludes, is one who cultivates harmony between the natures of their soul and allows them to be ruled by reason, just as a just republic is one that cultivates harmony between the different classes of citizens and promotes the rule of philosopher-kings.

Original Elitism

Only philosophers are in a position to know what is good, and “to know good is to do good,” so a rule by philosophers would, by definition, be good. Just as the reasoning part of the soul, if it understands a universal conception of good, will seek to do good. Or so he believed.

We can smile these days when we read about “parts of the soul” or other notions that have not been entertained for centuries, but some of Plato’s descriptions of societal degeneration are eerily insightful. It does seem, historically, that when societies have stumbled or fallen it was because they became ruled by something less than the better angels of their nature.

Reliving the Classics

We’ve seen many tyrannies evolve out of lawlessness, poverty and revolution. We can think of the times just after the French, Russian and Iranian revolutions, for example, when the underclasses looted all the wealth and destroyed all the art in sight. Plato would argue that Napoleon, Stalin and Khomeini were the inevitable consequences of impressionable people looking for a way out of anarchy and poverty.

In more modern times, we note that where we have attempted to “spread democracy” through nation-building, the resulting chaos has made the ground more fertile for charismatic warlords than for republican virtues.

John Locke

We’ve never seen a philosopher-king in our lifetimes, but the Founding Fathers (the closest thing we’ve experienced to actual public philosophers, and steeped in Platonic influence by way of John Locke) tried to set up a democratic way of selecting those for office who were most likely in the mold of the philosopher-king (rule of the “best and brightest”).

We contrast this with the direct democracy of Athens that Plato found so threatening. Plato believed that democracies emerge as a degeneration of superior regimes when the people become obsessed with superfluous, parochial interests and have no more use for universals like truth, justice or even honor.

The American Republic

In current political debate, the concept that seems most associated with America is freedom. We increasingly interpret this as a freedom to do what we want when we want, without interference, trade-offs, or much regard for social contract. I put this observation forward in a preceding post and David Brooks’s book The Social Animal. We can trace, starting with the sixties, a trend in moral and economic independence resulting in what Brooks calls the atomization of our society. So as we become more atomized, are we actually degenerating? Are we, in a very real sense, falling to the next lower level of what it means to be a society, and slipping further away from a sense of justice?

Related articles

-

- Philosophical Temperaments: From Plato to Foucault (wanderlustmind.com)

-

- Paralysed Democracy (darbarsenakranti.wordpress.com)

-

- Even Plato understood MGTOW (errantbuckeyeblog.wordpress.com)

- Utopia, where does it come from? (welcometoutopia2013.wordpress.com)

It’s always nice to come across someone who writes intelligently and in an engaging manner about philosophy.

Thank you! I appreciate your kind feedback.

This was interesting. I have been planning on reading The Republic.

Thank you for including a link to my page. I cannot take all the credit for it though, for Erudite Knight wrote the post that I reblogged here: http://eruditeknight.wordpress.com/2013/04/24/even-plato-understood-mgtow/

I enjoyed this post. It shows how remarkable Plato’s work is when it’s still applicable thousands of years later. Not only that, but thanks for connecting the Founding Fathers to philosophy. They certainly differed on now to build the country.

Errant: I like your observations very much. I agree that most classical writing, even if understood, is understood as a curiosity and not for its application to present thought. I am also down with MGTOW, an acronym I didn’t know existed until now.

Excellent parallels between Plato and today. I completely agree with the idea of atomisation and that after democracy the next step is tyranny. Look at pre-war germany. A booming country with an empire and excess wealth. By the end of the first world war it was completely broke. The Oligarchs had bled it dry and the populace democratically voted Hitler into power. After suffering aristocracy, timocrasy, oligarchy’s and now democracy, Germany fell into tyranny. This heralded the end of the empire of once great Germany. Not only that but after this all empires in the western hemisphere collapsed alongside them. This little example alone shows there is weight in Plato’s words.

Once fascism had been defeated in the world, the biggest threat to the world was Russia, our former ally who fought against the Nazi’s as well as the British and the American soldiers were now the enemy. Communism was the new threat. Maybe Russia were now at their timocrasy phase with Stalin who believed in higher morals. Unfortunately, this great soldier murdered his own people in cold blood. The Royal family had been murdered a few decades earlier, ending the aristocratic stage. Currently, the media tells us that Russia from the early 90’s has been run the Oligarchs.

In conclusion,I’m not agreeing with Plato blindly. We can all agree about one thing on Plato. He wasn’t a psychic. So if he could eerily warn of certain changes in our society its because he could accurately predict the actions of human nature and this is what has never changed. The logical course for the society is simple, for good actions there are good consequences and for bad actions there are only bad consequences.

Excellent breakdown, keep up the good work.